Jainism and the Art of Compassionate Living

Samani Sanmati stands in front of Mahavira’s image at Jain Vishwa Bharati of North America. Mahavira is the 24th Tirthankara, or spiritual teacher, of the Jains and is considered a role model for his ascetic lifestyle. Photo by Kohinur Khyum.

Jain monks’ nonviolent lifestyles are not limited to livestock. Samani Sanmati and her counterparts cover their mouths while speaking to ensure their breath does not hurt the microbes in the air. Photo by Kohinur Khyum.

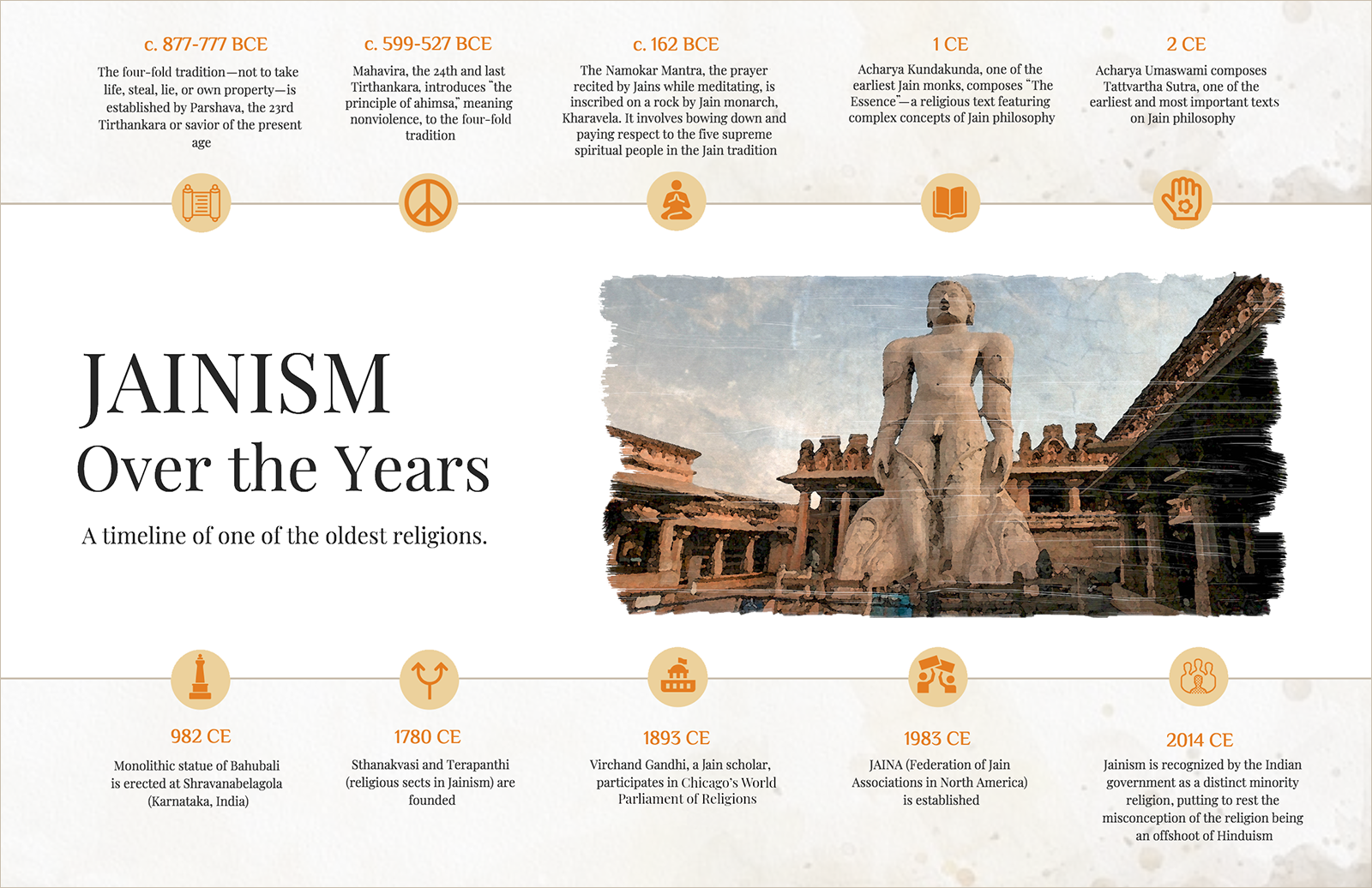

“The concept of compassionate living even predates Lord Mahaveer,” Sadhvi Pragya says. Its lifestyle revolves around the idea of compassionate living and austerity in order to attain salvation. Jainism became popular in India in the sixth century B.C. by Lord Mahaveer–a contemporary of Buddha–to counter the “brahminical” traditions, which had started dogging Hinduism and had stagnated. At the core of this faith lies the idea of salvation through nonviolence. Currently, there are roughly 100,000 Jain followers in the U.S., with roughly another 4.2 million people across the globe, mostly residing in India.

For Sadhvi Pragya, Jainism offers an escape. As a child, she enjoyed the arts. She painted, danced, and enjoyed doing skits, but her gender dictated a different path. “For any girl growing up at rural India during that time (pauses), she would be married off early,” she says. “My sisters were all married off.” So when Acharya Tulsi–her mother’s guru–took note of the sadhvi’s talents and offered her “diksha” — a ceremony involving the guru initiating a student into his teaching — she said yes.

“The austere lifestyle that we practice is not only meant for the enrichment of the body or soul, but to enrich our very existence.”

In order to become a monk, she had to undergo the training of her mind and body. Sadhvi Pragya went to Ladnun, India, to her guru’s training center. Initially, she says she signed up with the idea that she might not even make the cut. “But once at the training center, I was able to explore myself — and finish my long-cherished dream of receiving higher education,” she says.

But earning the opportunity to travel outside of India took time. Sadhvi Pragya says in the 1970s, Jain monks were barred from traveling in vehicles. So when a German delegation requested Acharya Tulsi to deliver a speech, he turned down the request. However, the invitation prompted him to create a new order of monks with a more relaxed approach toward traveling, and the sadhvi became part of that order. In the years that followed, she shared Jain philosophy and taught meditation and yoga to the followers of the faith. After years of traveling across the globe, she finally moved to New Jersey and has been residing there since JVB’s inception in 2003.

A Jain monk’s diet is an important part of their nonviolent lifestyle. Jain monks do not eat garlic or onion and consider them “hot” vegetables, meaning they believe it creates heat inside their body and disturbance in their mind. Photo by Kohinur Khyum.

Sadhvi Pragya says she is one of eight monks residing in the U.S. who belong to the order created by the sadhvi’s guru and are allowed to travel. She sits down to speak with us about Jainism, its connection to veganism, and how she puts compassion into practice.

NEHA: How would you describe Jainism’s concept of compassionate living?

Sadhvi Pragya: The concept of compassionate living even predates Lord Mahaveer. Here [the West] it is restricted to just food, but in Jainism, compassionate living encompasses every element that makes up our world. For example, Jains believe even water has life, so we don’t waste water. We believe in limiting water usage. The same goes for a plant-based diet. We believe in limiting our choices. That’s why we don’t consume root vegetables (onion, garlic, etc.). But more importantly, the idea of compassionate living, for us, is more of an idea. It’s a lifestyle mirroring the idea.

NEHA: How important is veganism/vegetarianism in Jainism?

S.P.: Jainism was founded on the idea of nonviolence. Eating non-veg is antithetical to the idea of “ahimsa” (nonviolence), so you can’t be a Jain. The emphasis is not on differentiating and prioritizing animals over plants. We are emphasizing more on life in general. Everyone wants to live but by “life,” we mean those with more developed sensory organs.

NEHA: Is there any difference in the practice in the West as compared to how veganism is practiced within the Jain community?

S.P.: The concept of veganism in the West is based on the idea of completely forsaking animal products. But our concept of daily diet is based solely out of “ahimsa” and respect for the others. We have gone to the extent of abandoning not just animal products but any form of food which is considered ananthkay [one body, but containing many lives] like root vegetables, sugar, and oil. There are other differences. Milk-based products aren’t part of a vegan diet. But in rural India, a cow is considered a sacred animal and is looked after as a household member. So we are against killing of cows for consumption, but rearing milk is not cruelty when observed from an Indian context.

NEHA: How important is meditation for the community?

S.P.: There are two aspects to meditation for the Jain community. One is for better health and the other for seeking truth. We often quote Lord Mahaveer and his thoughts on meditation. He believed his wasn’t the only way of seeking truth, as one has to find it by himself or herself, and meditation helps you to stay on the right path.

NEHA: Take us through a typical diet of a Jain monk. Does it stem from the austerity measures the monks practice?

S.P.: Our diet stems from the idea of a minimalistic lifestyle that we preach and practice. For a Jain monk, he or she typically has to fast 30 times a year. We fast in order to train and discipline our sensory organs. We believe only when one has complete control of his or her senses that one can internally link with our consciousness.

NEHA: There are a lot austerity measures in Jainism. How important is it for the body and soul?

S.P.: The austere lifestyle that we practice is not only meant for the enrichment of the body or soul, but to enrich our very existence. So body and soul can’t be taken in isolation. Rather, the two are a summation of our existence.

NEHA: On a different note, Buddha believed that real salvation lies in the soul. So all these austerity measures you practice, what’s the end goal?

S.P.: We don’t voluntarily submit to any form of penance. The word “penance” in the context of Jainism is often misconstrued. On the other hand, penance for the sake of penance is an act of cruelty in itself, and cruelty has no place in Jainism. While Buddha is right in a way, we believe that you still need austerity in certain cases. If your mind is trained enough, you don’t need to undergo any form of penance because you have control of your senses. But for an untrained mind, austerity helps in this regard.

NEHA: For those who are new to Jainism, what are typically the things they are most curious about?

S.P.: The first thing they ask me is why I’m using a handkerchief while talking. When we discuss our lifestyle, they are left wondering how someone can be at peace even while observing such an austere lifestyle. The monks have only two pairs of clothing with them and sleep on the floor as a form of tolerance while shunning luxurious items.

NEHA: What’s the biggest misconception about Jainism?

S.P.: The biggest misconception is that Jainism is an offshoot of Hinduism. The difference lies in the fact that Jainism is monotheistic in nature.

NEHA: If people are curious and want to learn more, are there any books you would recommend reading?

S.P.: That Which Is: Tattvartha Sutra by Nathmal Sutra and published by Harper Collins.

NEHA: How has practicing Jainism helped you understand the world?

S.P.: There is nothing absolute in nature. The word “absolute” is very relative and dependent on the context and from person to person. I have come to realize there are many truths, but it depends on what your point of view is.

Banner photo by Kohinur Khyum.