The Japanese Gardens That Grow Peace of Mind

As a travel experience, these gardens require a different mindset, Brown says, and are very different than observing the dusty columns of a great architectural achievement. Rather, Japanese gardens exist as living projects that demand attention, serving as peaceful reminders of the link between humans and their environment. “Fostering the garden is a term we now use, because like a child when it is born, it’s not finished; the parents have to raise it,” Brown says. “And if you want a Japanese garden, you have to build it, but you also have to raise it. I think everyone is coming to the mature realization that a garden is never really built. It is a process that takes time.”

In Japan, the evolutionary story of these gardens covers 14 centuries and features several different eras. So whether you are seeking a social day outside, a Zen temple for meditation, or a traditional tea ceremony, a garden exists for that purpose. And although Brown calls it “an impossible task,” he picked out one garden from several eras that typify their period. Most of the gardens reside in or around Kyoto, the country’s capital for more than 1,000 years, but notable gardens exist throughout Japan. Brown suggests these five as some of the best from their respective eras.

Jonangu: The Party Garden

This gem from the Heian period (794-1185) sits in southern Kyoto. Now surrounded by urban growth, the sanctuary garden represents the birth of the Japanese style of garden. These gardens feature multiple water elements, including large ponds and brooks that connected them. Centered around the meandering streams typical of the era, gardens such as Jonangu became places of meditation and socialization for aristocrats.

“To go to Jonangu, it’s not a festival—kind of a garden party. It’s a fun thing,” Brown says.

In fact, a common drinking game of the time involved floating cups of wine down the stream. As a cup arrived in front of a person, they would read a poem aloud. Any errors in the poem would result in a penalty cup of wine. After being rebuilt in the 1970s, this recreated site allows visitors to commune with nature, and each other, in a style around 1,000 years old.

Hours: Daily (March 20 – Sept. 30) 9 a.m. – 4:30 p.m.

Admission: 600 yen

Website: https://www.discoverkyoto.com/places-go/jonan-gu/

Daisen-in: Enter Zen

Moving into the 12th through 16th centuries, the Muromachi period saw the rise of the samurai class in Japan and ushered in the arrival of Zen Buddhism. Despite the violent occupation of their builders, Zen Buddhism left room for interpretation in meditation, creating this unique and varied style. Daisenin is a Zen subtemple housed within the larger Daitokuji temple complex in northern Kyoto. The temple houses five different gardens in connected courtyards, primarily featuring gravel and rocks with accompanying small trees and low-standing plants. As dry gardens, they lack the water elements typical of other eras but nonetheless aim to place worshippers within a peaceful, nature-invoking environment. “It suggests we move beyond gardens as a fun place to hang out and think about what people did in them,” Brown says. “There are new styles, diverse interpretations of the dry garden. Is it a three-dimensional landscape painting? Is it a mental puzzle, meant to be part of the Zen experience?” The space invites visitors to linger and contemplate their surroundings.

Hours: Daily 9 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Admission: 400 yen

Website: https://www.japan.travel/en/spot/1157/

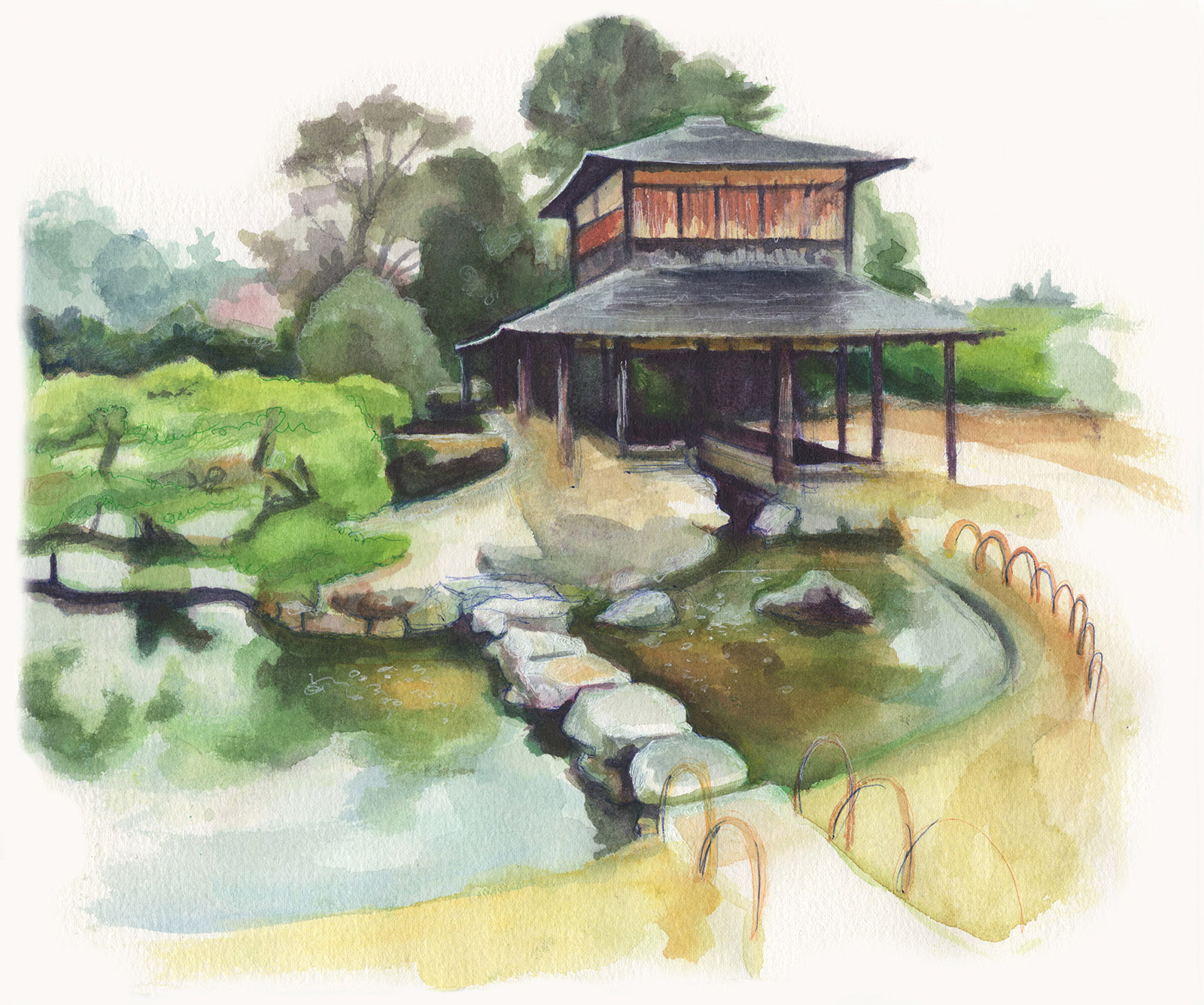

Sanbo-in: Tea To Go

The Sanbo-in subtemple within the Daigoji complex, located in Kyoto, covers about 5,000 square meters and features greenery surrounding a central pond. The bridges that divide the pond serve as a stage for more than 800 stones. “The garden is not just something that you are looking at, but something you are moving through,” Brown says of walking on the tea garden’s path, or roji. Built by the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi during a time of conflict, the calming landscape features decorative rocks claimed from defeated rivals. Based on the same spiritual relationship associated with Zen gardens, the tea gardens combine the contemplation of meditation with the physical, symbolic act of moving through the gardens leading up to outdoor tea ceremonies. “You are wetting your hands and purifying your mouth from the water basin. You are slowing down on the stepping stones because they are a little uneven,” Brown says. “You become very self-aware of your own being and the people around you.”

Hours: Daily (March – November) 9 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Admission: 600 yen

Website: https://www.japan.travel/en/spot/70/

Koraku-en: Status Symbol on a Stroll

The strolling gardens of the Edo period (1603-1868) reintroduced the opulence of the upper class, producing some of Japan’s most ornate and best-known gardens. Used as social gathering places for wealthy feudal lords, Brown says that the opulent gardens and their extensive landscaping represent a shift from aristocrats competing on the battlefield to instead competing in art and culture. “Often people want to take a photo without other people there. That’s kind of a false image because they were to be used in social events with people,” Brown says. “So again, try to put people into your experience of these gardens.” While Kenroku-en in Kanazawa and the Katsura villa in Kyoto were all famous gardens from the era, Brown also mentioned Koraku-en in Okayama. He suggests visiting in the fall to enjoy the autumn-colored grove and see the nearby lotuses bloom in a peaceful, social outing.

Hours: Daily (March 20 – Sept. 30) 7:30 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Admission: 400 yen

Website: http://okayama-korakuen.jp/english/index.html

D.T. Suzuki Museum: Monument to a Master

The increasing global cache of Japanese gardens in the last 150 years makes for a wealth of options both in Japan and abroad. But beyond the garden themselves, Brown also recommends the Suzuki Museum in Kanazawa, a recently completed exhibit dedicated to Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki. The grounds feature opportunities for visitors to read Suzuki’s work, including his famed Nihonteki Reisei (Japanese Spirituality), from books or iPads and ponder newly acquired knowledge in a modern but Zen space. The museum’s three buildings center around a pond that every two minutes drips one drop of water into an artificial pond; viewers are encouraged to consider the ripple effect that follows. “Its architecture, garden, and landscape space are really what you are experiencing,” Brown says. “Really it’s trying to use architecture and gardens to give you a sense of being in time and space in a mindful way.”

Hours: Tuesday-Sunday, 9 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Admission: 300 yen

Website: http://www.kanazawa-museum.jp/daisetz/english/